|

| Parliament buildings in Nairobi. Image: Courtesy |

Progress?

Stagnation? Or a combination of both? Just what description suits the state of

affairs of the Kenyan Republic 53 years after independence? I am not in the

business of being the jury and the judge at the same time but I endeavor to

present an analysis on the insincerity, machinations, dogmatism,

disillusionment, disparity, unfairness and hopefully the positives that outrightly

define and deeply describe the Kenyan polity.

There

is a common narrative in the public domain and more specifically in the developmental

circles regarding the similar state of socio-economic affairs between Kenya, the

Asian Tigers and the Tiger Cub economies in the 1960s, 70s and a better part of

the 1980s. Available information indicates that these economies’ challenges were

similar to Kenya’s in terms of the level of infrastructural development,

absolute and relative poverty rates among other socio-economic indicators. No

doubt that these Asian economies took-off while Kenya, a peer country at that

point in time, is still trying to find a balance on the developmental scale.

In

cognisant of the developmental differentials between Kenya and these Asian

countries in terms of the socio-economic complexities and dynamism, it is still

relevant and fundamentally important to thoroughly interrogate and investigate

where the rain began beating us. In any case, some degree of harshness is

required when evaluating a country which at one time was classified as a peer

economy to the Asian economies. Is it that Kenya’s progress, as envisaged at

the turn of the independence period, been hampered by certain intrinsic

factors, internally and externally?

The

Wabenzi Culture

|

| Members of the civil society protesting against corrupt leaders. Photo: Courtesy |

The

big man’s syndrome, the so-called wabenzi,

augmented with the get-rich-quick schemes since 1963 have often dragged Kenya’s

potential to be an economic powerhouse in Africa. The various administrations

and/or regimes that Kenya has had since attaining her independence have one common

denominator; corruption/embezzlement of public financial resources.

The

administrations of Jomo Kenyatta and Daniel Moi are a summation of 39 years of

cronyism. I strongly hold the view that Kenya would be a different country, in

positive terms, were it not for the malfeasance exercised during Jomo’s and

Moi’s regimes as the presidents of our Republic.

One

of the notable ideals that underpinned the struggle for Kenya’s clamour for

independence was indeed the maxim of economic independence in which all the

Kenyans irrespective of their ethnic, racial, gender or ideological orientations

were to be guaranteed equal economic rights. The Jomo Kenyatta administration

had the mandate of institutionalizing the independence manifesto in which economic

rights were to be keenly observed.

The

treachery that was employed by the Republic’s first administration under the

leadership of Jomo Kenyatta engendered a wicked culture in the country’s public

administration system. It was then that personal interest was placed above

public interest/service hence the entrenchment of the culture of amassing

wealth without any metric of accountability being taken into account.

There

is no doubt that Jomo Kenyatta and his cronies furthered the challenges of the

land question in Kenya which had initially been perpetuated by the

colonialists. The land question remains unresolved in this country since then

as the Republic has lacked a bold political leadership to right the wrongs

committed over 50 years ago.

These

economic crimes, of the illegal accumulation of wealth, were engineered by

honchos in the Kenyatta administration who were either politicians or

individuals who had strong political connections with the highest office in the

land. This is the point in time in which

Kenya’s politics was poisoned whereby it became the absolute pathway to

richness. Moi’s administration exacerbated the situation for 24 good years.

The

culture is still in place and perhaps the situation has even intensified. Across

the country, more than 90% of all the candidates for the various political

offices have only one main agenda; to utilize the opportunity of occupying a

political office to accumulate wealth.

Selective

Application of Justice

|

| Kenya's Judiciary. Photo: Courtesy |

Despite

the reformations that have taken place in the country’s justice system, more needs

to be done as far as the observation of the doctrine of the rule of law is

concerned. The principle of fairness and equality before the law changes tune

depending on how deep one’s pockets are or how well he/she is politically

connected.

It

is evident in this Republic that the economic and political elite are treated

differently than other citizens even when some members of the former group are

found to have planned and executed criminal offences especially the economic

crimes.

The

lords of graft who steal millions and billions of shillings are hardly locked up

behind bars compared to the high number of petty offenders who continue to fill

up the prisons. A good number of the officers within the justice system ranging

from judicial officers to law enforcement officers have oftentimes been bribed

to delay the administration of justice. These deliberately occasioned delays in

prosecution and jailing of the corrupt wealthy and mighty (The big fish) in

Kenya has always been an incentive for the increase in the rate of corruption.

The

selective application of justice has all along punctured the country’s economy;

it is an incentive for the politically connected individuals to steal public

resources which would otherwise have been invested in viable infrastructural

projects. As a matter of fact, how can serious private investors have

confidence in the government if economic crimes aren’t punished heavily? This

is a concern for the private investors with regard to property rights.

Haunted

by the Ghosts of the 1960s

|

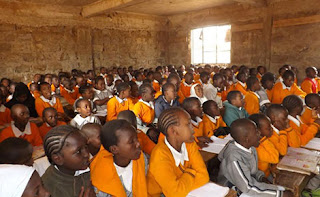

| Pupils in a congested public primary school. Courtesy: Standard Media |

At

the turn of independence, the then government was focused on eradicating three

notable challenges; poverty, disease and ignorance by institutionalizing viable

economic policies, establishing an effective healthcare system, and setting up an

efficient education system. As a matter of fact, a national blueprint, African Socialism and its Application to

Planning in Kenya, was drafted to fast-track the process of achieving the

targets set by the then government.

Unfortunately,

the development plan was never fully implemented and the same fate faced the

subsequent policy frameworks formulated to improve the living standards of the

citizenry as I illustrated in a previous article. Significant strides have been

made in the course of the last 50 plus years of independence but there is lot

that needs to be done to tackle poverty, improving healthcare and the education

standards.

As

much as there has been progress in the education sector, the government must be

committed in improving the conditions especially in most of the public primary

schools. These schools have a poor teacher-pupil ratio, dilapidated facilities

and a chronic shortage of learning equipments. I am longing for the day that

most members of the political elite, the upper-middle class and the wealthy

will take pride in enrolling their children in public primary schools.

The

conditions in the public health facilities must be greatly improved for the

benefit of all the citizens. The political leadership; the Executive and

Parliament, has never been fully committed in establishing a universal

healthcare system in the country. The political class doesn’t even have

confidence in the public healthcare system because it is ill-equipped. This has

contributed to medical tourism where each year there is an increase in the

number of patients traveling to countries such as India to seek for medication.

The billions of shillings looted in the Ministry of Health in each fiscal year

is enough to set up modern health facilities that are fully equipped with

modern machinery for treating the non-communicable diseases such as cancer,

diabetes, and others which are on the rise.

Tribalism:

The Dark Paradise

|

| An IDP camp following the 2007/08 PEV. Photo: Courtesy |

Negative

ethnicity is real in Kenya with a good number of socio-economic and political

arrangements/deliberations taking shape along the ethnic divisions. Since

independence, the successive governments have been characterized with deeply

entrenched tribalism as a result of the “we” versus “them” mentality. This has

really worked against the realization of Kenya as a one united nation.

Kenya’s

politics is largely based on ethnicity. In a nutshell, the doctrine of

ethnicization of the political system is pronounced in our Republic. Just as I have

noted earlier in this article, most of the challenges experienced in Kenya can

be traced to the first post-colonial government and these mistakes haven’t been

rectified by the successive governments.

Tribalism

isn’t confined to politics but it is alive and kicking in other structures of

the Kenyan polity especially regarding employment opportunities, awarding of tenders

and contracts or even access to public services which all the citizens are

entitled to.

Negative

ethnicity has troubled our Republic and this has significantly hindered

economic progress. Following the 1992 general elections, there were ethnic

clashes that took place and even the 1997 elections had certain parts of the

country recording ethnic flare-ups. Despite the fact that the 2002 general elections

were peaceful, regions such as Kuresoi in Nakuru County experienced ethnic

clashes. The mother of all ethnic explosions rocked the country in 2007 following

the disputed results of the presidential elections. The 2007/08 post-election

violence (PEV) was much more than the election results; the existing unfair distribution

of national resources was the primary factor precipitated by the “we” versus “them”

mentality.

Taking

into account that the PEV was our Republic’s critical juncture in restructuring

the systemic challenge of negative ethnicity, profound measures such as the

formation of the Truth Justice and Reconciliation Commission (TJRC) and the

enactment of a new Constitution were put in place. To ensure that there is fairness

in the distribution and redistribution of national resources, the aspect of

devolution was indoctrinated in the Constitution. However, the tragedy has been

the failure by the political leadership to implement the recommendations of the

TJRC report and this puts the country at risk of another major ethnic outburst.

Various

parts of the country continue to witness occasional fighting among some of the communities.

These cases are common among the Pokot, Turkana and Marakwet communities; along

the border of the Kipsigis-Kisii, Luo-Nandi, Kisii-Maasai, Kipsigis-Maasai, and

Orma-Pokomo among others. The fights have disrupted the economic activities in

these regions.

The

Economy: A Distorted & Non-Inclusive Complexity

|

| Jua kali artisans. Courtesy: Business Daily |

The

economy is growing but hardly developing; the rate of structural transformation

in Kenya’s economy has been extremely slow. This is why cases of extreme and/or

absolute poverty continue to be on the increase. Of course the national

government and its honchos will always viciously defend the economy’s progress

but their defense is anchored on the estimates of the Gross Domestic Product

(GDP) which is a foggy way of analyzing the economic progress of any economy.

Developed

and the newly industrializing economies experienced structural transformation

due to the fact that their governments were committed in making heavy

investments in the manufacturing sector. Kenya’s manufacturing sector currently

makes up 11% of the country’s GDP compared to 16% in the 1970s and part of the

80s. This decline is largely due to the lack of bold political leadership to

effectively implement the development blueprints/economic policy frameworks and

also the Bretton Woods institutions (IMF, World Bank) are partly to be blamed

following the fantastic failure of the Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs)

back in the 1980s.

At

the moment our economy is faced with the twin deficit problem; trade deficit

and fiscal deficit. The trade deficit has been occasioned by a large volume of

imports compared to the relatively lower volume of exports as a result of

lacking a vibrant manufacturing sector. The fiscal deficit has increased

tremendously under the Jubilee administration presenting a possibility of a

debt overhang.

The

major reason why Kenya resorts to borrow largely to finance its expenditure is

because of the low levels of savings within the economy. Savings play a crucial

role in financing investment projects and in due course cushioning the economy

against the shocks that may emanate in the case of the externally sourced

funds. Currently, the level of savings in Kenya is around 14% which is low for

any economy seeking to have a strong economy.

Kenya’s

economy is largely reliant on the informal sector and this has significantly

contributed to the rising levels of unemployment. More jobs are created in the

informal sector compared to those created in the formal sector. Unemployment is

a ticking time-bomb and in any case a concern for the country’s political

stability. The frustrated, unemployed “army” is a threat to national security.

History has shown that economic frustrations are bound to generate political

turmoil in a polity.

Food

security, as detailed in an article co-authored by my colleague and I, is still

a major challenge to the government fifty-plus years down the line. The

successive governments have always adopted reactionary measures in approaching

the issue of food insecurity and it seems learning from history has been a tall

order for the country’s political leadership.

So,

where do we stand as a country? Are we on the path to prosperity? Is the political

leadership committed to transforming the country’s economic landscape? Find the

right the answers.

This article was first published on blog.savicltd.co.ke.